| Model Classification | Refactored Classification |

|---|---|

| Southeast Asian, East Asian | Asian |

| Middle Eastern, Latino_Hispanic | Other |

3 Methods

As described in the previous section, the two selected models (DeepFace and FairFace) are run on the UTK face dataset in order to generate output of classification across 3 categories (age, race, and gender). We evaluate the performance of this classification, and perform hypothesis testing in order to answer the key research questions.

3.1 Data Cleaning: Standardizing Model Outputs

As can be seen in Chapter 2, there are some key differences between the outputs of both models as well as the source data that we needed to resolve to enable comparison of each dataset to one another. We’ll focus on the primary features of age, gender, and race from each dataset.

3.1.1 FairFace Output Modifications

We’ll discuss FairFace first, as it introduces a requirement for modification to both our input information as well as the outputs for DeepFace.

Age: FairFace only provides a categorical predicted age range as opposed to a specific numeric age. We retain this age format and modify the last category of “70+” to “70-130” to ensure we can capture the gamut of all input and output ages in all datasets.

Gender: No changes to predicted values; use “Male” and “Female”

Race: the source data from UTKFace has 5 categories “White” “Black” “Asian” “Indian” and “Other”. Using the definitions from UTKFace, we collapse the output categories of FairFace’s Fair7 model as follows:

3.1.2 DeepFace Output Modifications

Age: Cut the predicted age into bins based upon the same prediction ranges provided by FairFace. If the DeepFace predicted age falls into a range provided by FairFace, provide that as the predicted age range for DeepFace.

Gender: we adjust the DeepFace gender prediction outputs to match that of the source and FairFace data.

Race: we adjust the DeepFace race prediction outputs to match that of the source dataset.

Our refactoring is as follows for DeepFace:

| Model Classification | Refactored Classification |

|---|---|

| woman | Female |

| man | Male |

| white | White |

| black | Black |

| indian | Indian |

| asian | Asian |

| middle eastern, latino hispanic | Other |

3.1.3 Source Data Modifications

Age: We cut the predicted age into bins based upon the same prediction ranges provided by FairFace. If the input / source data age falls into a range provided by FairFace, provide that is the source age range for the image subject.

Gender: No changes.

Race: No changes.

3.2 Exploratory Data Analysis (EDA)

Our EDA performed on the source UTK dataset can be seen in the previous section in Figure 2.2. The EDA performed on the output from the models can be summarized as follows, and is presented in the Results section:

- Visualization of the histograms of distributions of predictions, per each category, per each model

We also perform some meta-analysis on the statistics and performance metrics calculated from the model outputs:

- Visualization of the p-values vs F1-score across all hypothesis tests across both models

- Confusion matrix of whether we reject or fail to reject the null hypothesis based on power and F1 score

3.3 Hypothesis Testing

Our data consists of three main sets: the source input data, the Fairface output data, and the Deepface output data.

We’ll be creating our hypothesis tests by running as two-sample proportion tests. The population is the set of all labels (of race, age, and gender as defined below) for a given image, for all face images. The first sample will be the source dataset “correct” labels of the images, and the 2nd sample will be the output of a given model between FairFace and DeepFace, respectively. The base null hypothesis will produce no difference in sample proportions. Gaining a statistically significant result would allow us to reject our null hypothesis in favor of the alternative hypothesis.

In other words, rejecting the original assumption means there is a statistically large enough difference between the source data and output data, and could indicate that the source and predicted information originate from differing populations, which is a potential indicator of bias for or against the protected classes in question. We use a significance level of 99.7% to mitigate the risk of rejecting the the null hypothesis when it is true.

We’ll be testing across different subsets contained within the data, as listed below:

3.3.1 Demographics

- Age Group

- Gender

- Race

3.3.2 Demographics’ Subgroups

- Age Group (9 groups)

- 0-2

- 3-9

- 10-19

- 20-29

- 30-39

- 40-49

- 50-59

- 60-69

- 70-130

- Gender (2 groups)

- Female

- Male

- Race (5 groups)

- Asian

- Black

- Indian

- Other

- White

3.3.3 The General Proportion Tests

Our hypothesis tests will be testing different proportions within these subgroups between the source data and the output data.

The general format of our hypothesis tests will be:

\(H_0: p_1 = p_2\)

\(H_A: p_1 \neq p_2\)

With the following test statistic:

\[ \dfrac{(\hat p_1 - \hat p_2)}{\sqrt{ \hat p (1 - \hat p) (\dfrac{1}{n_{p_1}} + \dfrac{1}{n_{p_2}}})} \]

With the p-value being calculated by:

\(P(|Z| > z | H_0)\)

\(= P\bigg(|Z| > \dfrac{(\hat p_1 - \hat p_2)}{\sqrt{ \hat p (1 - \hat p) (\dfrac{1}{n_{p_1}} + \dfrac{1}{n_{p_2}}})}\bigg)\),

With

\(\hat p = \dfrac{\hat p_1 * n_{p_1} + \hat p_2 * n_{p_2}}{n_{p_1} + n_{p_2}}\)

Where:

- \(p_1\) = the source dataset categories labels given and \(p_2\) = the chosen model’s labels given.

- \(\hat p\) = the pooled proportion.

- \(n_{p_1}, n_{p_2}\) = the size of each sample.

We also calculate the power of each test performed, and use a power level threshold of 0.8 in order to assess the strength of the p-value calculated.

Our research explores the possiblity of using two-sample proportion testing as a means by which one could evaluate the performance of a machine learning model; we are uncertain as to whether or not it is appropriate. In leveraging two-sample proportion tests, we can infer whether the proportions of age, gender, or race (or some combination thereof) from the UTKFace dataset (i.e. 1st sample) originate from the same population as the outputs from each facial recognition model (i.e. 2nd dataset).

In theory, substantial differences in proportions of protected classes between the two datasets could suggest that the source data and predicted data originate from differing populations (pictures of people on the internet), and could thus indicate presence of bias against the protected class in question.

Leveraging p-values and powers calculated on our samples for our protected classes of age, gender, and race, may enable us to identify biases that may manifest from one or both models. Leveraging F1 scores (as described below) will help us identify specific cases of bias, and whether they are in favor of or against a specific group.

3.3.4 Notation

We introduce notation for the specific tests we perform:

Let \(R\) be race, then \(R \in \{Asian, Black, Indian, Other, White\} = \{A, B, I, O, W\}\)

Let \(G\) be gender, then \(G \in \{Female, Male\} = \{F, M\}\)

Let \(A\) be age, then \(A \in \{[0,2], [3,9], [10,19], [20,29], [30,39], [40,49], [50,59], [60,69], [70,130]\};\) or \(A = \{1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9\}\)

Let \(D\) be the dataset, then \(D \in \{Source, Fairface, Deepface\} = \{D_0, D_f, D_d\}\)

3.3.5 Proportion Testing of Subsets

Using this notation, we can simplify our nomenclature for testing a certain proportion of an overall demographic.

For example, we can test if the proportion of Female in the Fairface output is statistically different than the proportion of Female from the source.

Hypothesis Test:

\(H_0: p_{F, D_f} = p_{F,D_0}\)

\(H_A: p_{F, D_f} \neq p_{F,D_0}\)

P-value Calculation:

\(P\bigg(|Z| > \dfrac{(\hat p_1 - \hat p_2)}{\sqrt{ \hat p (1 - \hat p) (\dfrac{1}{n_{p_1}} + \dfrac{1}{n_{p_2}}})}\bigg)\),

where

- \(\hat p_1 = p_{F, D_0}\): proportion of females from the source data

- \(\hat{p_2} = p_{F, D_f}\): proportion of females from the FairFace output

Additionally, we could test for different combinations of subsets within demographics. For instance, if we wanted to test for a statistically significant difference between the proportion of those who Female, given that they were Black, as predicted by DeepFace, then we could write a hypothesis test like:

\(H_0: p_{D_d, F|B} = p_{D_0, F|B}\)

\(H_A: p_{D_d, F|B} \neq p_{D_0, F|B}\)

These were two specific hypothesis tests, however, we’ll be testing all combinations of these parameters and reporting back on any significant findings.

In the above, we’ve outlined our methods for examining a total of 432 hypothesis tests per recognition model on the totality of, and smaller samples of, our overall dataset. We have elected to sub-divide our source and predicted samples by these protected classes to inspect and investigate bias against groupings of protected classes.

For instance, in the performance of our hypothesis tests, we may find lack of evidence for a bias when only examining proportions of gender between samples. However, by examining a subset of our samples, such as subject gender given the subject’s membership in a specific racial category, we may find biases in predictions of subject gender given their membership in a specific racial group.

This could help us answer questions and draw conclusions about such groups. Examples of conclusions could include:

“Model X demonstrates bias in predicting the race of older subjects.” Such a statement is not one of bias for or against the target group, but that a bias exists. A bias in either direction, if used in a decision-making process, could result in age discrimination.

“Model Y demonstrates bias in predicting gender, given the subject is Black, Asian, or Other.” Such a statement is not one of bias for or against the target groups, but a statement that a bias exists. Such a bias, if used in a decision-making process, could result in gender or racial discrimination.

Structuring our tests in this manner enables us to quickly analyze and report on the results of our tests.

3.4 Performance Measurement

We evaluate the performance of the models in order to choose which models to use (as described in the Data section), to ensure data integrity, and to evaluate the hypothesis testing in context of performance. These measures are not used in the calculation of the statistical/hypothesis testing.

There are four main measures of performance when evaluating a model:

- Accuracy

- Precision

- Recall

- F1-Score

Each of these performance measures has their own place in evaluating models; in order to explain the differences between these metrics, we start with concepts of positive and negative outcomes.

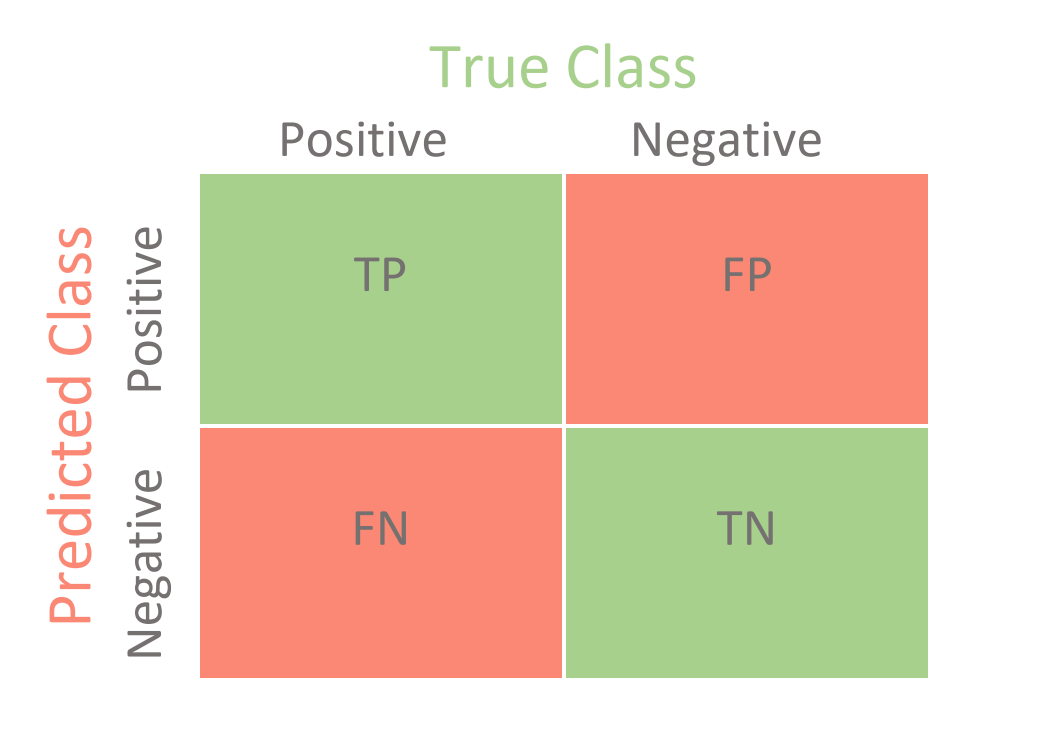

- True Positive: predicted positive, was actually positive (correct)

- False Positive: predicted positive, was actually negative (incorrect)

- True Negative: predicted negative, was actually negative (correct)

- False Negative: predicted negative, was actually positive (incorrect)

These outcomes can be visualized in a confusion matrix. In Figure 3.1, green are correct predictions while red are incorrect predictions.

3.4.1 Accuracy

Accuracy is the ratio of correct predictions to all predictions. In other words, the total of the green squares divided by the entire matrix. This is arguably the most common concept of measuring performance. It ranges from 0-1 with 1 being the best performance.

\(Acccuracy = \frac{TP+TN}{TP + TN + FP + FN}\)

3.4.2 Precision

Precision is the ratio of true positives to the total number of positives (true positive + true negative).

3.4.3 Recall

Recall is the ratio of true positives to the number of total correct predictions (true positive + false negative).

3.4.4 F1-Score

F1-Score* is known as the harmonic mean between precision and recall. Precision and Recall are useful in their own rights, but the F1-Score is useful in the fact it’s a balanced combination of both precision and recall. It ranges from 0-1 with 1 being the best performance.

F1-Score \(= \frac{2 * Precision * Recall}{Precision + Recall}\)

When considering the classification of a subject by protected classes of age, gender, and race, we believe that stronger penalties should be assigned in making an improper classification decision. Due to F1 being the harmonic mean of precision and recall, incorrect classification will more directly impact the score of each model in its prediction of protected classes, and do so more strongly than an accuracy calculation (Huilgol 2021).

We calculate F1 score as a measure of performance of our selected machine learning models. F1 scores will not be considered when evaluating the results of our hypothesis testing or impact them in any way. We will compare our results for F1 score against our hypothesis test results to examine possibility of correlation or fit of proportionality tests as a means for predicting model performance. Separately, we will leverage F1 scores to examine biases for or against protected classes.